By Erin O’Gorman

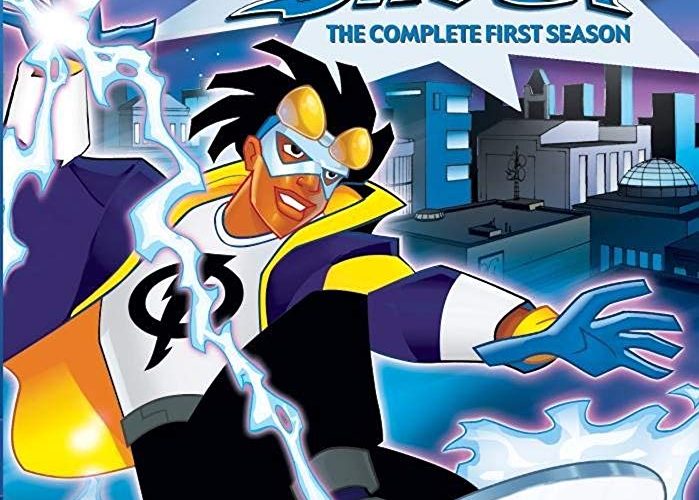

Rewatching a beloved childhood television program after almost 20 years can kind of feel like the early 2000s threw up on you, and I mean that in the most positive way I can. At least it’s how I would begin to describe the four seasons of Static Shock, a short-lived but well remembered animated program about an African American teenager who becomes a superhero after receiving the power to control electricity, that ran from 2000 to 2004.

We begin in what quickly seems to be a fictional equivalent of Detroit, which has been renamed Dakota City (Shock to the System, season 1, episode 1). From the start, Virgil – our superhero- is a morally stable nuclear sort of student who displays an above average intelligence, he is well-liked enough by his peers, chows down on Burger Fool while avoiding the wrath of his tyrannical older sister and trying his best to be the morally upstanding citizen his father wants him to be, in a city overrun by gang violence that killed Virgil’s mother five years prior to the pilot. But of course this isn’t Degrassi, it’s a superhero show, so what’s the catch?

The plot device that sets off the entire story is a toxic explosion of quantum vapor gas that causes grotesque mutations in those who are exposed to its fumes. This incident is nicknamed ‘the Big Bang’ and extends to its superpowered victims being called ‘bang babies’. They don’t go into detail or explain why the formula was created in the first place and it is written off as a freak accident. But yet it seems all too coincidental to freely keep such potent material in an area that appears to be notorious for its use of gang battlegrounds. In fact, the gas explosion scene felt reminiscent of seeing clips of historical racial riots when protestors were beaten and tear-gassed, almost as if the writers drew inspiration from those struggles. All of these events take place in episode one, where poor Virgil is simply in the wrong place at the wrong time after white bully, Hotstreak, tempts him to join a gang for protection. His error is one he has no idea will end up being his greatest blessing, as he watches with horror the others grotesquely mutate, while he himself is just a tad too close to a wired telephone pole while trying to escape.

The messages in the show are amazingly and subtly sewed into the show’s plotlines, in four seasons they managed to tackle issues of poverty, gang violence, gun violence, homelessness, racism, mental illness stigma, bullying, dyslexia, dealing with the emotional grief from the loss of a parent and so much more. Much of this can be reflected by the 2000 economic crash which likely triggered a chain reaction since homelessness, organized violence, and poverty are all tied to a loss of stable finances. Unfortunately, the aftermath of this is, loss of family to violence, depression, being unable to afford medication and treatment for other condition. It’s a brilliant tie that I think a lot of shows fail to do when attempting to represent real-life problems.

The seriousness is well balanced with a number of silly cameos that would rival the amount Scooby Doo had. I can’t decide if my favorite was Lil Romeo or the NBA stars (Hoop Squad, season four, episode seven) written in as part of a secret superhero organization. Putting current celebrities in TV shows is a brilliant and subtle marketing strategy for keeping ratings relevant, especially when they are people like NBA stars who young viewers look up to as their real-life heroes, so why not write them in as superheroes? The same concept goes for Lil Romeo’s appearance in season three (Romeo in the Mix) as that episode featured two songs from the newest album he’d released at the time.

Any ‘90s child who watched this back in the day will agree that one of the most easily remembered episodes is ‘Sons of the Fathers’ in season one when Virgil finds out his best friend and sidekick Richie Foley, has a hardcore racist father. It begins when Virgil realizes that Richie has never invited him to his home in all their years of their friendship, feeling guilty about this Richie offers for him to come for a weekend sleepover. Richie does this under the assumption his father is working a night shift but it doesn’t work out that way and upon Mr. Foley’s first onscreen appearance, it’s pretty easy to tell what his views on people of color are; even before he mumbles ‘not nearly enough’, as his son introduces them while reminding that he’s told him about him before. All of it is brushed off by Virgil as dad grumpiness since he can’t picture his beloved best friend being tied to an ideology that hates him for his skin color until a very awkward dinner shortly later. The spark begins with Virgil trying to break a confusingly tense meal by mentioning to Richie a new rap album he bought over for them to listen to. The whole thing sets Mr. Foley on a rant about his dislike for hip hop culture and him stereotyping it as teaching kids to misbehave and, in his own words, that it “tears down everything guys like him built”. Again, Virgil brushes it off as an old generation thing as opposed to a racial thing. He refuses to see it until he walks past Richie’s parents’ bedroom and overhears Mr. Foley tells Mrs. Foley “that kids a bad influence”, while referring to Virgil, and that “all his kind are – its bad enough I have to deal with them all day and now one is in my house!” Ironically, the horror on Virgil’s face as he listens reflects the horror that was on Mr. Foley’s face earlier in a bizarre way.

It’s in fact almost eerie the way his spoken hate, poor judgment and intolerance mirror the voices of pro-Trump supporters in the 2016 elections. I mention poor judgment because there’s a scene where Robert, Virgil’s father, and Mr. Foley are in a rundown building talking to a group of homeless teenagers while looking for Richie who ran away from home after an argument with his father. The kids aren’t causing any trouble per se but the fact they’re dressed in “hip-hop clothing” gives grounds for them to quickly be judged by Mr. Foleyfor their appearance.

Amid his snide commentary, Robert, who is the head counselor at the city community center, explains that just because a teenager has spiky green hair and would rather hang out in certain areas because they don’t get along with their parents doesn’t mean they’re a criminal or a bad person. What’s displayed here is a concept that’s been around probably since the development of complex civilization. The nature and evolution of humans will always cause old generations to look down upon the styles of the newer generations, whether that be in the form of neon hair, arms full of tattoos or low slung pants. I feel that what the writers were trying to make the audience look beyond the bigger picture in terms of racism, that such an idea is one dimension that makes up the concept of intolerance. It’s the first part in a lesson of tolerance for Richie’s dad that you wish everyone beyond animation could understand. It’s also why it’s so satisfying to see Robert later tell him off about being proud of his bigotry.

On a much less gritty note, I thoroughly enjoyed the episode in season three portraying Anansi the Spider from West African folklore as a mystical powered Zorro of sorts; seen as a hero by the people of Ghana and learning about the rich Ashanti culture there and seeing how proud Virgil and his family were to be of African descent. According to Mythology.com, Anansi is a spider who is a trickster and practical joker with the ability to tell stories. A child of the personified Earth and Sky, he holds a spiritual power in all things because of this. In essence, he isn’t just one being or person which makes how the show portrays him so characteristically androgynous, all the more interesting. Unlike many of the heroes who have assisted Static in previous or post episodes we never learn his true identity even when he makes another appearance in a future episode.

It was lovely to see was the depiction of a bustling modern African city, as I feel that many media portrayals only show the savannah or small villages outside the city which leads people to assume that’s all there is in Africa. There’s definitely an educational aspect here, as we learn that Ghana was a British colony at one point until it became independent in 1957. We also learn that the capital city Accra – where the family is visiting – is home to the burial site of civil rights leader W.E.B. Du Bois who was a major supporter of pan Africanism, a belief that unites all black people and their cultural connection to Africa. The writers did an excellent job of properly executing this episode by using the lore of Anansi as a heroic figurehead to play out the pride of Africans.

In general, the way Robert, Virgil and his sister Sharon were placed was favorable because it doesn’t make any assumptions about what a black family or a single black parent is like. Sharon is just a girl trying to put herself through college while juggling helping her father run the house in her mother’s absence. Mr. Hawkins is often strained between balancing his often emotionally demanding job and being a parent to two children; it’s all realistically standard, but nothing racially biased or stereotypical.

The development of Virgil/Static as a superhero from the opening season to the very last is also realistically standard as we see him go through a ‘Dark Knight’/Christopher Nolan sort of development when he learns that being a superhero isn’t always easy. This is particularly true after his love interest gets hurt and ends up in a coma because of a mistake he made thanks to his briefly over-inflated ego. His growth ebbs and flows but by the series last scene, where he and Richie are flying off through the city together, he has jumped far from being the scrub that followed around Batman and Robin.

It’s really a shame we couldn’t get more than four seasons of this gem which was so well received in its day. Nobody really knows why it was canceled, though there is speculation that many toy companies did not feel that the general public would buy merchandise from a show about a black superhero and so the producers possibly felt it wasn’t worth the investment if it couldn’t be mass marketed.

“American animation costs more to make than can be recouped from network licensing fees. That means that for a show to be profitable, it needs other revenue streams like toys, clothing, novelties, et cetera,” Static Shock creator, Dwayne McDuffie said in an interview with Worlds Finest, “Static Shock enjoyed massive ratings throughout its run. In its final season on Kids WB, only Pokemon consistently outperformed it. When it moved to Cartoon Network in reruns, it did even better, initially finishing just behind Family Guy. One single Friday night episode did a 5.2 rating. That meant 5 million people were watching it at the same time. Staggering when you consider that the comic book ran 45 issues and only sold a couple million copies combined. Despite this, Static was unable to attract toy companies or other licensors. After five years, we had a Subway value meal, two Scholastic book adaptations, one DVD and a Gameboy Advance game (that so far hasn’t been released). We couldn’t even get DC to do a Static Adventure-style comic book. Without these monies coming in, it was a gift to get to do 52 episodes.”

However, considering the growing popularity of superhero television and the strong call for diverse representation in media today, we can only hope that Netflix or Hulu plan on a revival soon. For those of you who don’t want to wait, ‘Static Shock’ is available through the 7.99 a month subscription on DCUniverse.