While one can’t legally purchase alcohol or gain a commercial driver’s license (CDL) until 21 years of age in the U.S, turning 18 marks a significant landmark throughout most societies, allowing individuals to vote, take authority of investments or junior savings accounts, and prepare for study at a higher education institution.

A young Malik, or Mark T. Watson as he was known prior to embracing Islam, was contending with not only a new age of 18, which bestowed a myriad of profound privileges and responsibilities, but he was also grappling with miscarriages of justice that adversely impacted his childhood and early adolescent years.

‘’I had spent 9 years as a Child in Care (CIC) the equivalent of what they call the group homes in the US. This had come as a result of the disability of my father who was a Guyanese seaman in the 1930s, fought the nazis during the war on behalf of the British as a volunteer and settled in England after the war and had his children in 1960s Liverpool’’ reveals Malik.

Amidst a time when signs were ingrained with rhetoric such as ‘No dogs, no Irish, no Blacks’, Malik’s father, comparable to many other Black seamen in the Liverpool district, purchased a house, with no mortgage, as Malik’s father was in a position to own the house entirely mortgage-free in Toxteth, an area that Malik smiles before stating that ‘’it was right in the heart of the Black community.’’

Unfortunately, in 1969, the local council imposed a Compulsory Purchase Order (CPO), which is something that Mailk insists occurred throughout Black communities within the UK to disseminate them. Consequently, Malik and his family were removed from their familiar dwellings to a location that consisted of 100,000 White families with a paltry 4 Black families.

Within the U.S, a policy known as eminent domain allows the central government to seize private property and compensate the owners. Often, even when compensated, the money would be far less than the property’s true value. In Mailk’s case, his father was unable to afford to purchase a house of the same calibre for what the local council ‘compensated’ him with.

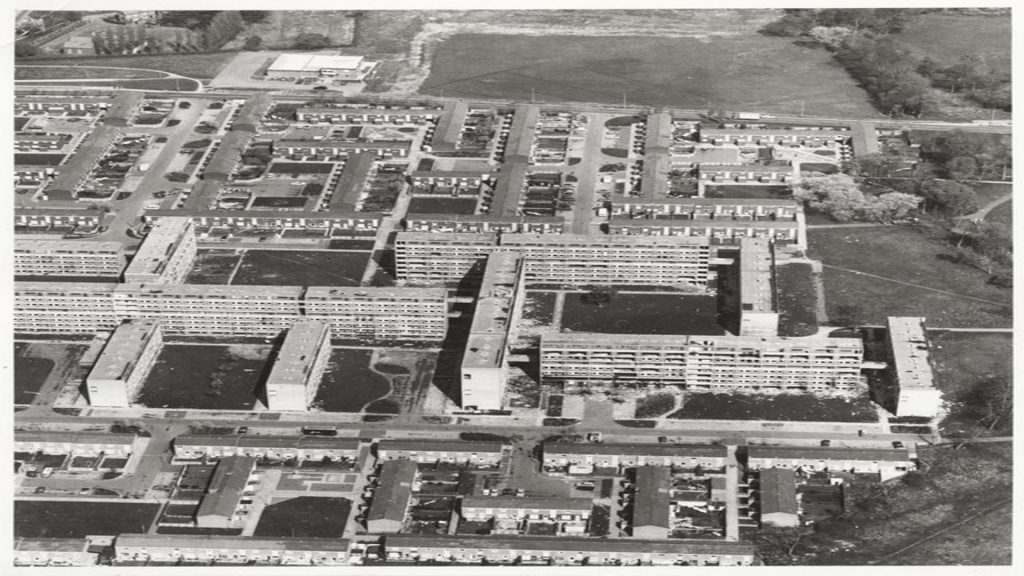

1970s Estate – Peckmill Green Brittage Brow in Netherley where Malik’s family where dispersed post-CPO

In some cases, thriving communities with banks, theatres, cinemas, restaurants, doctor surgeries, schools and tailors, such as the Black Wall Streets in Sweet Auburn, Atlanta; Durham, North Carolina; Richmond in Virginia; Broward County in Florida; Chicago’s Bronzeville; and the more famous Tulsa in Oklahoma, were annihilated by fascist organisations such as the Ku Klux Klan.

Malik argues that such polices were being implemented both within the U.S and the UK ‘’to ensure that Black communities never became cohesive. Black communities never became economically viable, and Black people were forced to assimilate into White society.’’

After Mailk’s father had a stroke in 1974, which led to his developing quadriplegia, his mom was left to attend to four Black children. Scornfully, social workers would categorically say to Malik’s mom, who is White ‘’Why don’t you give us your Black kids and find yourself and find a nice White man and have a proper family’’ says the PhD candidate who is making the last amendments to his thesis at University of Cambridge. Malik’s mom resisted for as long as possible, but the financial and mental strain curtailed overwhelmed her, and consequently two of her children ended up in the care system, Malik in 1975 and his brother in 1978.

Though far from opulent, Malik came from a family of economic stability entwined with traditional values and the hard work ethic of the Guyanese. Malik was now at the mercy of a multitude of care homes where he was inflicted with “forced labour, racial abuse and physical abuse. I was actually taken and put in solitary confinement at the age of 9 as well’’ confesses Malik.

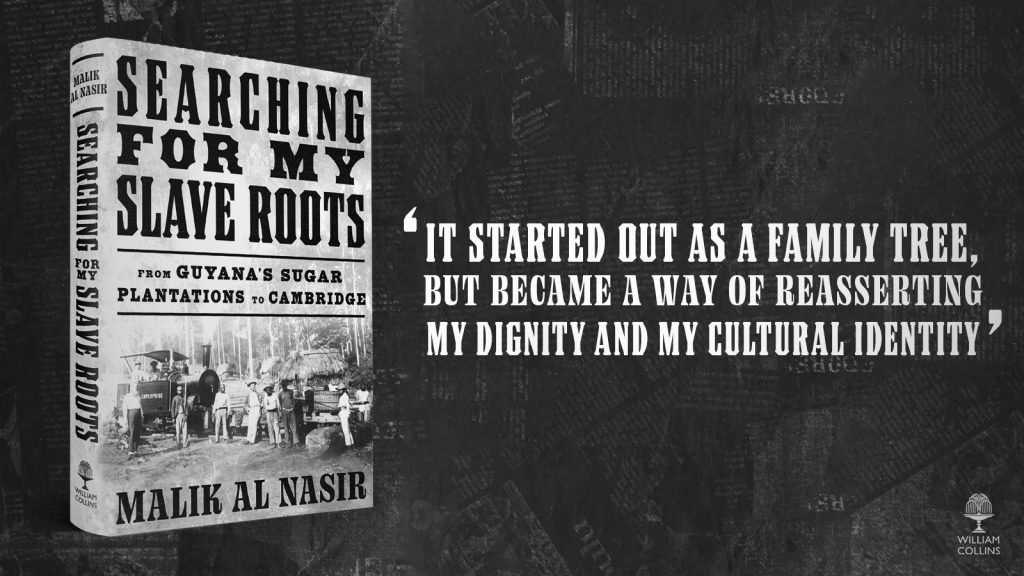

Malik, who wrote Searching for My Slave Roots: From Guyana’s Sugar Plantations to Cambridge, has never been one to surrender to injustice. His callous treatment at the hands of local social services led Malik to sue Liverpool City Council for his abominable treatment. Successfully suing Liverpool City Council was a laborious process, which took 10 years of litigation.

The justice that Malik sought is, however, arguably insurmountable. When a young Malik was 18, he was released from the care system, feral, being placed in the wilderness, unprepared for what lay ahead. He was domiciled in a hostel for Black youths in Toxteth, a place from which he was now estranged. The social services had not adhered to any duty of care, relinquishing any responsibility and coercing Malik to sign a form not to request additional money after being given £100.

‘’By this time, my father had died. My connections to my Guyanese community, my connections to my Black roots, had completely gone. I had not grown up in the Black community, but I had now been placed back into the Black community’’ Malik graphically reveals. Without making explicit reference, and with a pause, followed by a deep sigh, Malik accurately illustrates his predicament, quoting what the Jamaican national hero Marcus Garvey said is ‘’like a tree with no roots.”

One of the most deleterious implications of Malik’s 9 years in care was that his educational potential was arrested. ‘’I was semi-literate’’ declares the soon-to-be Cambridge PhD graduate. While chattel slavery has supposedly been abolished in the UK, Malik said: ‘’I had spent most of my time, many years working as a child slave labourer on a farm, instead of being in class. As a consequence of that, I was struggling to read and write.’’

Influenced tremendously by the renowned spoken word, singer/songwriter and self-proclaimed “Bluesologist”, Gil Scott-Heron, Malik was drawn to Gil, who played an instrumental role in Black civil rights activism. Many of Gil’s songs, such as Winter in America; Angola, Louisiana; and the famously poetically charged The Revolution Will Not Be Televised; served as a soundtrack to the life of Black America in the 1970s when many of the songs were released.

A decade later, into the 1980s, Mark, who would have been still a teenager, vividly remembers when uprisings erupted across English cities such as the 1980 St Pauls uprising in Bristol and the more prominent 1981 Brixton London uprisings in April, the Birmingham inner city uprisings in Handsworth, and other notable uprisings in Chapeltown Leeds and Moss Side Manchester during the same year.

Chronologically sandwiched between the Brixton and Handsworth uprisings, Toxteth in Liverpool had its own uprisings, which broke out on a humid July evening. The uprisings in Toxteth, a vicinity in which Mark was born and was now residing in, were a response to the attempted arrest by police officers of photographer and poet Leroy Cooper, who passed away in 2023.

‘’He [Leroy Cooper] was wrongfully arrested by the police, and they roughed him up, and the community reacted, and the Toxteth riots started. Following on from the Toxteth riots, we had what became known as the long hot summer of 1981, where communities across the UK rose up in response to police brutality against Black communities’’ says Malik.

Known by some community activists as the turbulent 80s, where further uprisings flared in 1985 in Handsworth, Brixton and Broadwater Farm Tottenham throughout the month of September and early October, this epoch can be contextualised with the policies that were being implemented by the then prime minister Margaret Thatcher in what the late cultural theorist and sociologist, Stuart Hall coined Thatcherism and across the waters with Ronald Regan’s Reaganomics, who was serving as the United States president.

‘’There was a lot of racial tension. There was a lot of racial polarisation that was happening at that time. So, that was the context in which Gill [Scott-Heron] came to England in 1984, just three years after the riots [1981]. When he was arriving, people in Liverpool treated it as if he were a diplomatic representative of the Black community that was arriving to hear our grievances’’ says Malik, the author of Letters to Gil.

As a result, prior to performing at the Royal Court Theatre in Liverpool, Gil Scott met and spoke with key figures and individuals in the city, including The Liverpool 8 Black Caucus and The Liverpool 8 Defence Committee. The numerical reference to 8 signifies the L8 postcode, where most of Liverpool’s Black community resided during this period.

Malik’s brother told him of Gil’s concert and encouraged him to attend, hoping he might attain some direction when Gil Scott-Heron visited the city. With an absence of money and no concert ticket, Malik headed to the venue where Gil was due to perform. Sighting a friend of his, who worked as a professional photographer, would be how Malik would enter the venue. ‘’Meeting Gil was the beginning of what would be a lifelong relationship. Of mentorship, guidance, direction which lasted right up until Gil passed away’’ says Mailk.

This was a revitalisation point in Malik’s life. He became self-educated, harnessed his skills as a talented poet, and transitioned into academia, graduating from all three of Liverpool’s universities, including a Russell Group institution, and is currently in the final stages of earning a doctorate in History at the University of Cambridge.

An exhibition – Toxteth: The Harlem of Europe honouring Black musicians from the 1950s and 1960s will be on display until August 1st, 2026.